Decision-Maker’s Dilemma: What We Know vs. What We Believe

Why Uncertainty and Ambiguity Shape Every Choice We Make

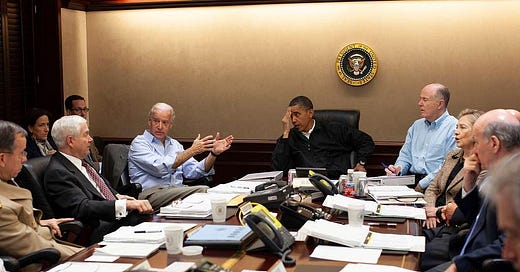

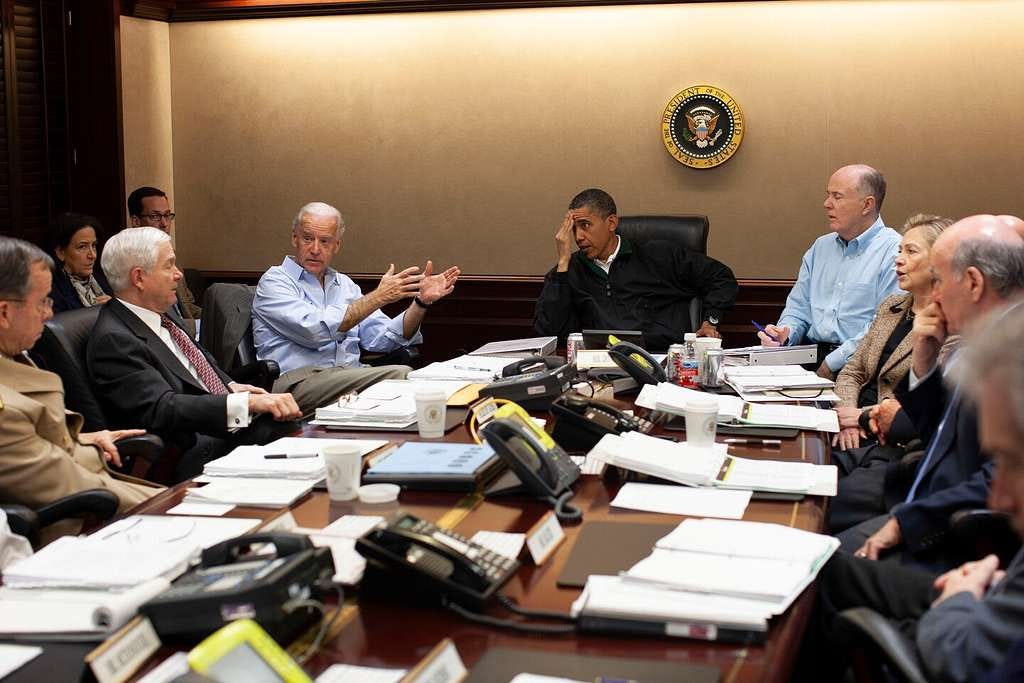

In 2011, President Barack Obama faced a high-stakes decision—whether to authorize a raid on a compound in Pakistan suspected of hiding Osama bin Laden. The intelligence suggested a strong possibility that bin Laden was there, but it wasn’t certain. Some reports put the probability at about 55%. If the assessment was wrong, the U.S. would be launching a military operation in another country, risking American lives, and straining diplomatic relations for nothing. If it was right, the raid would take down the architect of 9/11 attacks.

This incident captures the two fundamental challenges of decision-making: uncertainty and ambiguity.

Uncertainty is about what we don’t know. Obama faced epistemic uncertainty (whether bin Laden was in the compound) and inherent randomness (random factors like weather, equipment failure, or enemy resistance; sometimes refer to as aleatoric uncertainty).

Ambiguity is about how the same situation can be interpreted differently. Some advisors framed the raid as a necessary risk, others worried it could destabilize U.S.-Pakistan relations, and some suggested alternative approaches like a drone strike.

Ultimately, President Obama made the call, and the mission succeeded. But this wasn’t just a military decision—it was a case study in navigating uncertainty and ambiguity. This dilemma is not unique to military operations; it plays out in diplomacy, business, and even everyday life.

Whether it's responding to changing climate, managing international conflicts, or making personal financial choices, decision-makers face two fundamental challenges: uncertainty and ambiguity. Understanding these concepts and how to navigate them can mean the difference between well-informed, adaptable strategies and costly, ineffective decisions.

Understanding Uncertainty

Uncertainty arises when we lack complete knowledge about future outcomes. It comes in two primary forms: epistemic uncertainty and inherent randomness.

Epistemic uncertainty refers to a lack of knowledge or missing information about a situation. It can often be reduced by gathering more data, improving models, or increasing expertise. However, until the knowledge gap is closed, decisions must be made based on the best available information.

Inherent randomness, on the other hand, refers to uncertainty that cannot be eliminated, even with better knowledge. Some events are shaped by chance—factors like weather conditions, mechanical failures, or unexpected human actions—that introduce unavoidable risks. Since these uncertainties can’t be eliminated, decision-makers must plan for them—using probabilistic assessments, contingency strategies, and flexible decision-making.

Both types of uncertainty were central to Barack Obama’s decision to authorize the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound. Intelligence estimates suggested a 55% probability that bin Laden was there—a case of epistemic uncertainty, where more information might have improved confidence. Even if the intelligence was correct, there was still inherent randomness—mechanical failures, enemy resistance, or unexpected complications could have caused the mission to fail, no matter how much intelligence were gathered or how well the mission was planned.

This dual nature of uncertainty affects nearly all decisions. Recognizing whether uncertainty stems from a lack of knowledge or inherent randomness helps decision-makers apply the right strategies—whether refining intelligence or preparing for unpredictable risks.

Understanding Ambiguity

Ambiguity, on the other hand, occurs when different people interpret the same situation in conflicting ways. Unlike uncertainty, which deals with missing information or randomness, ambiguity stems from differences in values, priorities, and perspectives. It is not just about lacking information; it’s about conflicting perceptions of what matters.

Within the context of Obama’s decision to raid the compound, ambiguity played a crucial role in shaping public, political, and international responses. The mission was not just a question of whether Osama bin Laden was there (epistemic uncertainty) or whether the operation would succeed (inherent randomness); it was also a matter of how different stakeholders framed the decision based on their values, norms, and geopolitical interests. Does the United States have the right to attack someone in another sovereign country? Was Pakistan complicit, negligent, or unaware? Did the mission strengthen or weaken U.S.-Pakistan relations? How should the outcome of the mission be framed politically?

Each of these interpretations reflects ambiguity, not uncertainty—it was not about missing information but about differing priorities, perspectives, and stakes in the decision. While uncertainty can sometimes be reduced through better intelligence and modeling, addressing ambiguity requires diplomatic negotiation, narrative framing, and stakeholder engagement to navigate effectively.

A relatable personal example of ambiguity may focus on deciding whether to take a new job in a different city. One person might see it as an exciting opportunity for career growth, while their partner views it as a disruptive move that could affect their own career and social life. The uncertainty—such as how the new role will actually turn out—can be evaluated more or less objectively by researching the company, talking to current employees, or evaluating industry trends. However, the ambiguity—how the move aligns with different life priorities and personal values—requires a problem-solving mindset that balances competing priorities—an approach central to engineering diplomacy.

While uncertainty can sometimes be resolved with better information, ambiguity requires dialogue, perspective-taking, and decision-making frameworks that acknowledge competing priorities.

The Nile Water Dispute: How Uncertainty and Ambiguity is Playing Out

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile River exemplifies how uncertainty and ambiguity shape international negotiations.

Uncertainty comes from climate change and hydrological variability, making it difficult to predict long-term water availability for downstream countries, particularly Egypt and Sudan.

Ambiguity arises because Ethiopia views the dam as a sovereign right to development, while Egypt sees it as a threat to its water security. Sudan oscillates between economic benefits and flood risks.

Efforts to resolve this conflict require not only quantitative modeling to predict water flow but also diplomatic negotiation to reconcile competing narratives. Decision-making frameworks that integrate uncertainty modeling with stakeholder engagement offer ways to bridge technical and political divides.

COVID-19 Pandemic Response: The Science-Policy Divide

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic were characterized by significant uncertainty and ambiguity.

Uncertainty was present because scientists lacked definitive data on infection rates, transmission dynamics, and vaccine efficacy. Models projected different scenarios based on evolving information.

Ambiguity surfaced as policymakers faced conflicting public priorities—some valued strict public health measures, while others prioritized economic stability and individual freedoms.

Countries that navigated this complexity well, such as South Korea and Taiwan, combined adaptive science-driven policies to address uncertainty with transparent public communication and consensus-building to manage ambiguity. In contrast, nations that framed COVID-19 solely as a scientific problem without addressing societal ambiguity faced political backlash, misinformation, and reduced public compliance.

Personal Financial Planning: Uncertainty & Ambiguity in Everyday Life

Uncertainty and ambiguity aren’t just for world leaders and policymakers—they affect decisions in our personal lives as well.

Imagine you receive an inheritance of $450,000 and must decide how to invest it.

Uncertainty comes from financial markets being unpredictable. Future interest rates, inflation trends, and stock market performance are unknown.

Ambiguity arises because different financial advisors offer conflicting recommendations. Some emphasize long-term growth through stocks, while others prioritize safety in bonds or real estate. Your personal values, such as risk tolerance, ethical investing, and financial goals, further shape the decision.

A good strategy balances data-driven risk assessment to manage uncertainty with clarity on personal priorities and trade-offs to navigate ambiguity.

What This Means for Decision-Making

The Decision-Making Under Uncertainty and Ambiguity framework argues that we need:

Scientific and probabilistic tools to navigate uncertainty, as seen in hydrological models for the Nile dispute or epidemiological forecasts for COVID.

Stakeholder engagement and negotiation strategies to resolve ambiguity, as in diplomatic water-sharing agreements or public health messaging.

Adaptive, pragmatic approaches that blend engineering rigor with diplomatic flexibility—an essential part of engineering diplomacy.

The world is not a deterministic system where a single "best" solution exists. Instead, we need decision-making processes that are resilient, inclusive, and adaptive. Whether managing a transboundary river, handling a global health crisis, or making personal investment choices, understanding uncertainty and ambiguity is key to making better decisions.

What’s Next?

In the future editions of Engineering Diplomacy, we will explore real-world strategies for navigating uncertainty and ambiguity—drawing insights from game theory, behavioral science, and case studies in engineering diplomacy.

What’s a decision in your life or work where you’ve struggled with uncertainty and ambiguity? I’d love to hear your thoughts and insights.