Decision-Maker’s Dilemma: Lessons from Game Theory

How to Navigate Uncertainty and Ambiguity of Decision-Making

In our last edition, Decision-Maker’s Dilemma: What We Know vs. What We Believe, we explored how uncertainty and ambiguity shape decision-making, from international diplomacy to personal finance. This time let’s take it a step further—what happens when uncertainty and ambiguity aren’t just challenges to overcome but factors that can be carefully managed and leveraged in decision-making.

Game theory offers a fascinating way to think about decision-making when the future is unclear. It’s about understanding the nature of uncertainty, anticipating what others might do, weighing risks, and making the best possible move given the information you have. Whether it’s a geopolitical standoff, an economic power struggle, or a salary negotiation, game theory helps explain why people and nations behave the way they do—and how you can make smarter choices when faced with uncertainty and ambiguity.

Game Theory: Different Faces of Decision-Making

The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Rational Actor Model?

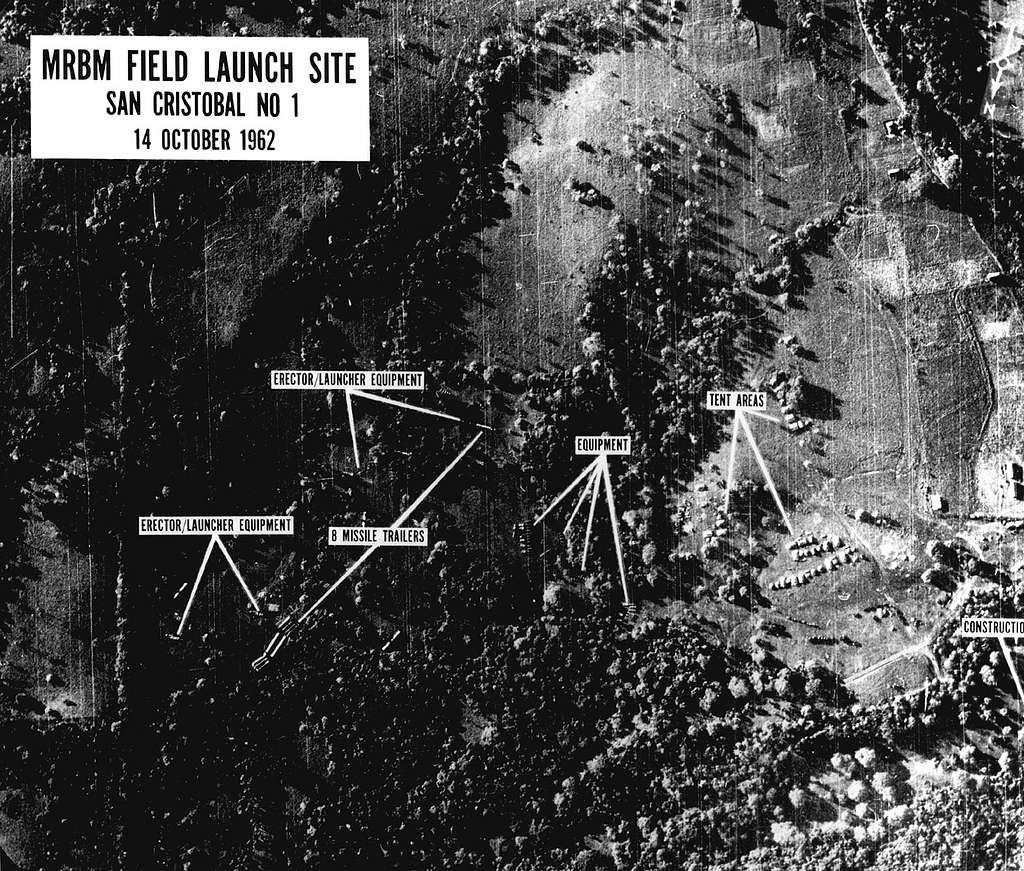

For thirteen days in October 1962, the world was on the edge of nuclear war. The discovery of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba put the United States in an agonizing position: how should it respond? The stakes couldn’t have been higher—any miscalculation could have led to global catastrophe.

For President Kennedy, the situation was a classic case of uncertainty and ambiguity. He didn’t know if the Soviets were willing to risk war (uncertainty), and within his own administration, advisors debated whether the missiles were a defensive move or an act of aggression (ambiguity).

If you ask a game theorist or an economist, they might say that the U.S. acted rationally—that President Kennedy and his advisors carefully weighed the risks and rewards of various options before choosing the most strategic move. Kennedy’s team debated five main responses, each with its own risks:

Do Nothing – Rejected quickly. Accepting Soviet missiles in Cuba would signal weakness and embolden Khrushchev.

Diplomatic Pressure – Too slow and uncertain. The Soviets could stall while the missiles became operational.

Naval Blockade (Chosen Option) – A measured response that demonstrated U.S. resolve while keeping war at bay.

Surgical Air Strikes – Could eliminate the missiles but risked Soviet retaliation, possibly triggering war.

Full-Scale Invasion – The riskiest option, likely leading to direct conflict with the Soviet Union.

The blockade was the middle ground—it showed strength, forced Khrushchev to respond, and left room for negotiation. And it worked. The Soviets backed down, removing their missiles in exchange for a quiet U.S. withdrawal of missiles from Turkey.

The rational model helps explain why the U.S. made the choices it did, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. Governments aren’t single, unified minds—they are collections of institutions, personalities, and competing interests. With this in mind, it’s important to step back and ask: does rational decision-making always lead to the best outcome? To test this, let’s look at two other scenarios—one involving economic strategy, the other a personal negotiation—where rationality doesn’t always work as expected.

OPEC and the Limits of Rational Self-Interest

If the Cuban Missile Crisis was a game of rational brinkmanship, the global oil market is a game of cooperation and betrayal. At its core, OPEC (the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) is an ongoing prisoner’s dilemma—a situation where acting in your own short-term interest can lead to worse outcomes for everyone in the long run.

OPEC members have a shared goal: keeping oil prices high. If all members restrict production, supply stays low, and prices remain strong. The problem? Every individual country has an incentive to cheat—to quietly increase production, sell more oil, and make extra profit while others hold back.

From a rational choice perspective, each country should act in its own self-interest. But when too many members do this, oil prices collapse, and everyone suffers. Rationality at the individual level leads to collective failure.

Unlike the Cuban crisis, which was a one-time strategic showdown, OPEC is an ongoing game. Countries must consider not just today’s profits, but how their choices will affect future cooperation. OPEC tries to manage this by using agreements and quotas, but the reality is that trust and enforcement mechanisms are just as important as rational calculations.

So, while game theory helps explain the incentives, it doesn’t always mimic real-world behavior. If rationality alone determined outcomes, OPEC would either collapse from defection or be perfectly stable—but instead, we see cycles of cooperation, cheating, and enforcement that reflect something more complex than pure rational logic.

This brings us to another example—one that many of us face on a personal level.

Salary Negotiation: The Rational Player vs. Human Behavior

Imagine you just received a job offer. You’re excited, but you have a decision to make: should you negotiate for a higher salary?

If we apply the rational choice model, the answer is simple: always negotiate. If the employer has budgeted more for the role, you’re leaving money on the table by not asking. The worst they can say is no, right?

And yet, many people hesitate.

Why? Because, in reality, uncertainty and ambiguity shape our choices just as much as rational strategy does.

Uncertainty: You don’t know how much flexibility the employer has. Will they walk away if you push too hard?

Ambiguity: You’re getting conflicting advice. Some people say to be aggressive, others warn against appearing “difficult.” Fear of rejection, power dynamics, and even personality traits influence how we approach negotiations.

The rational model gives us a useful framework, but in real-world salary negotiations, outcomes depend on more than just logic. Just as with OPEC, trust, reputation, and long-term relationships all play a role.

This is why successful negotiators don’t just maximize numbers—they read the situation, adapt their strategy, and create the perception of value. Signaling confidence, having justifications, and knowing when to push or pull back are just as important as the “rational” decision itself. This is where uncertainty and ambiguity need to meet to make effective decision-making for desirable outcomes.

What These Games Teach Us

The Cuban Missile Crisis, OPEC, and salary negotiation all highlight different ways we make decisions under uncertainty and ambiguity:

In Cuba, the rational choice model largely holds up—the U.S. acted strategically to force a resolution without war.

In OPEC, rational self-interest leads to suboptimal outcomes, showing the limits of pure game theory when cooperation is required.

In salary negotiation, rationality is important, but ambiguity of perception, relationships, short- and long-term interests shape real-world choices.

This game-theory motivated examples tell us something important: while the rational model is a powerful tool, it isn’t always enough. Decisions aren’t made in a vacuum—they happen in complex environments with multiple players, competing incentives, and imperfect information.

And this is exactly why Graham Allison proposed two additional models to explain the Cuban Missile Crisis—ones that consider bureaucratic infighting, organizational inertia, and institutional power struggles. Because sometimes, the right move isn’t just about logic—it’s about the messy, human reality of decision-making under uncertainty and ambiguity.

We’ll explore those models in the next piece. But for now, I’m curious:

Have you ever faced a decision where the “rational” choice didn’t feel right?

Can you think of a situation where both uncertainty and ambiguity shaped your decision?

Do you think decision-makers actually behave as rational actors, or do other factors play a bigger role?